Anonymous is a loose collective of internet users that took umbrage at the Church of Scientology's removal of the infamous Tom Cruise video from YouTube. The collective's ongoing battles against internet censorship made CoS culture of secrecy an ideal adversary. Following the wisdom of Mark Bunker, they organised a worldwide protest on February 11th to mark the birthday of Lisa McPherson. McPherson had been suffering from either some form of mental illness or a real desire to be free from the organisation. Either way, whilst in the care of the organisation she died in circumstances that remain mysterious. What is certain is that she was restrained against her will, was refusing to eat or drink, and on her collapse was not rushed to the nearest hospital, but to a hospital further away where a Scientologist was on the staff. But I digress.

I was aware of the planned demonstrations, and knew of the two London sites at which I could attend, but chose not to for a variety of reasons. The first and most important reasons comes down to who the demonstration is for. The parallel here, I suppose, is with narcotics. The message you give to people who haven't used narcotics is different to the message you give to addicts. You warn the people who haven't used that they could lose their health, wealth and happiness, but you tell the people who are addicted that they could get that all back again. I was concerned that the demo would be sending the wrong message to the wrong people.

Furthermore it is easy to see a large demonstration as being there for the wrong reasons. One can have the best intentions in the world when trying to engage with Scientologists, but if they decide from the outset that you are a suppressive person then everything you say will be for nothing.

Lastly, the demo was effectively an unknown quantity, personally at least. I didn't know who it was that I'd be siding with. There can be a fine line between a legitimate and peaceful protest and a hate rally.

As it turned out, however, the demos went without serious incident, save for an accident in Ohio, and generally the responses to the day's protests were positive. Comments were made about how well behaved everyone was, that they were polite and for the most part respectful. I wouldn't say I regretted not going, but the reports of the first demo helped inform my opinion for the second set of demonstrations scheduled for March 15th.

Initially I'd hoped to go along unmasked and photograph and write up the demo, and keep an eye out for any of the infiltrations that CoS were rumoured to have planned. But on Friday I had to reconsider my strategy. In part this was due to the way in which Co$ had singled out unrelated individuals in their failed attempts at an injunction ahead of the March demos. Also, I didn't want my presence there to be misconstrued by Anonymous. If I didn't wear a mask, Anon would reasonably assume I was photographing the event on behalf of CoS, and CoS would reasonably assume that, as I was unknown to them, I was with Anonymous, and therefore would be worth (and have a marginally higher than average probability of) identifying. So on Friday I purchased one of the few remaining V masks in London, making it clear on which side of the street I intended to stand.

I masked up a little way from Blackfriars, feeling terribly self-conscious about it, and slightly paranoid about wearing a mask on public transport. I was comforted early on, bumping into someone masking up, and made my way with him along to Queen Victoria Street where Anonymous had commandeered a stretch of pavement and the balcony above, directly opposite the Celebrity Centre. The theme for the March demo was Hubbard's birthday, and to this end there were party hats, blowers, and much cake was provided, along with attendant slogans such as "we have cake, Scientology has lies".

There were a couple of hundred people there already, but this number was added to slowly and continually throughout the day. Part of the Anonymous draw is the "lulz", a corruption of LOL, and there was a large amount of internet meme to be seen interspersed with the more on topic placards on display. There were various chants from the serious "Why is Lisa dead?" to the amusing. The Celebrity Centre suffers for being next door to a church, leading to a choreographed bout of pointing, "This is a church, this is a cult," a chant reminiscent of Scientology's so-called locational processing assist. Such fun kept the energy of the demonstration at a high for the three hours prior to moving off to Tottenham Court Road; a journey consisting of many conversations on exactly how they would fit the protesters into the smaller site opposite the Dianetics Centre, and how to get to Tottenham Court Road.

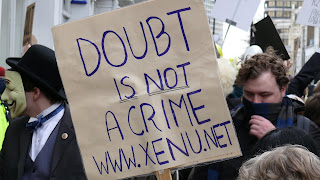

The TCR protest involved the same chants, more or less, being called out to what appeared to be most of the same org staff. The protest became long and thin, running along the opposite pavement. The foot and road traffic on Tottenham Court Road is much more dense, and Anonymous were able to distribute a great deal of information about the Church to passers by, occasionally cheering as motorists honked their support. It is the dissemination of information about the Fair Game Policy, Operations Freak Out and Snow White, Lisa McPherson, the RPF and key websites (Ex-Scientology Kids, Xenu.net, whyaretheydead.net, Stop Narconon, etc.) that really makes the demonstrations worthwhile. Added to that is the newsworthiness of the Anonymous movement, which has served to place the media spotlight on the policies and crimes of the Church.

The above slogan was perhaps my favourite of the day. Scientology is a closure of thought, where doubt isn't tolerated unless it is extended to anything other than itself. Those who have left, high OTs included, all speak of lengthy periods of doubt, and the difference between waking up or staying in seems to be knowing what to do with that doubt. That is why it is so important to provide the doubtful with information of quality and a support network so that they know that when they walk there are people that are ready and willing to help them.

The next round of demonstrations, scheduled for April will focus on reconnection, of getting folk that are in and have disconnected to get back in touch with their families and friends. I'm not sure how Anonymous will balance the lulz with the heartache of disconnection, but it will hopefully lead to a more tangible result, and the possibility that a family, even just one, will be reunited because of events that were set in motion because Co$ bullied YouTube is a very attractive one indeed.